When the World is Alive: Indigenous Language, Verbs, and a Different Way of Seeing

Modern life is shaped by the language we speak. Words don’t just describe the world – they frame how we perceive it. In English, nouns dominate. We live surrounded by “things”: the tree, the river, the mountain, the stone. Each is pinned down like a specimen, frozen in time and space, turned into an object that can be categorized, owned, or used.

This grammar reflects a Western worldview: nature as backdrop, resource, or raw material. It is a world of objects that exist for human use. But the Indigenous worldview is different. Many indigenous languages, such as Potawatomi, structure reality differently. Instead of being noun-heavy, they are verb-rich. In Potawatomi, as Robin Wall Kimmerer explains in Braiding Sweetgrass, nearly 70% of the language is built from verbs. A bay is not a “thing” but wiikwegamaa – “to be a bay.” The maple is not simply a noun but “maple-ing.” The forest is “foresting.”

This difference may sound small, but it reflects an entirely different way of seeing the world – one that could help us rethink our relationship to the Earth at a time of ecological crisis.

A World in Motion

To live in a language of verbs is to inhabit a world that is always moving. Nothing is static. Rocks hold the warmth of the sun. Rivers carve their way forward. Soil breathes and feeds. Birds are not “things” that can be captured in a category; they are beings engaged in the act of birding – flying, singing, nesting, migrating.

This verb-based grammar refuses to let reality be reduced to dead objects. Instead, everything is alive, active, and in motion. The emphasis is not on what something is, but on what it is doing and how it is relating.

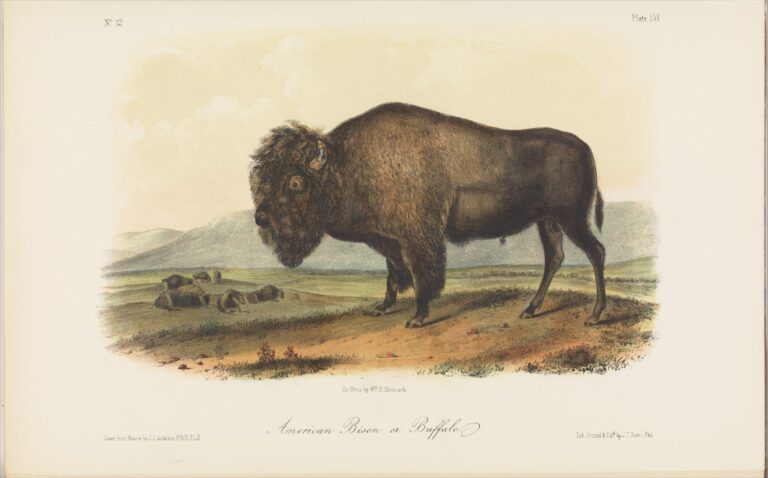

In English, by contrast, we strip beings of their motion. A bird becomes a noun, an “it.” A river is fixed as a thing to be measured, dammed, or diverted. A tree becomes “timber.” This subtle linguistic habit shapes our mindset: we forget that we live inside a living system of relationships, not among a warehouse of objects.

Peoples, Not Things

In many Indigenous traditions, personhood is not confined to humans. Animals, plants, rivers, stones, winds, and mountains are all considered peoples. They are not metaphorical characters but real beings with agency, intelligence, and responsibilities within the community of life.

This worldview is encoded directly into grammar. In Potawatomi, beings are either animate or inanimate. You cannot refer to a maple tree, a bear, or a heron as “it.” To do so would be a kind of grammatical violence, a denial of their personhood. Instead, these beings are animate relatives, deserving the same respect as human kin.

This is not romanticism; it is recognition. A maple tree is not a passive thing. It is engaged in photosynthesis, storing sugars, drawing up water, sheltering birds, and gifting oxygen. A river is not just a line on a map; it shapes valleys, carries nutrients, and sustains entire communities of beings. A heron is not an “it” but a being with its own will and place in the web of life.

When you see other species as peoples, your relationship to them changes. You no longer ask only, What can I take? You also ask, What do I owe?

Reciprocity as a Way of Life

This verb-centered language shapes a verb-centered ethic. To live in a world of animate beings is to live in a world of responsibilities.

Indigenous worldviews consistently emphasize reciprocity – the principle that humans are not separate from the rest of life but participants in it. You take only what is needed. You give thanks. You offer something back. This is not superstition or sentimentality. It is a practical recognition of interdependence.

A hunter offers tobacco or prayer to the animal whose life will sustain them. A forager takes from a patch of berries but leaves enough for the birds and for the plants to renew themselves. A farmer enriches the soil with compost and ceremony, recognizing that without healthy soil there can be no healthy people.

This ethic stands in stark contrast to the Western economic worldview, where forests are “timber stocks,” animals are “resources,” and rivers are “water rights.” In a system dominated by nouns and ownership, the world is something to be extracted. In a system dominated by verbs and relationships, the world is something to be cared for.

Western Contrast: The Grammar of Extraction

Western languages and philosophies, shaped by industrialization and colonization, tend to reduce living beings to objects. A forest is not “foresting,” it is “timber.” A river is not “flowing,” it is “water supply.” A fish is not “fish-ing,” it is “stock.”

This objectifying mindset makes it easy to justify exploitation. When the Earth is a warehouse of resources, humans stand outside of nature as managers and consumers. When the Earth is alive with peoples, humans stand inside a community of relations, accountable for their actions.

The consequences of the Western worldview are all around us: deforestation, extinction, climate destabilization, poisoned waters. These are not accidents; they are the logical outcomes of treating beings as “its” rather than “thous.”

Why It Matters Today

We live in a time of profound ecological crisis. Species are vanishing at rates unseen since the last mass extinction. Climate patterns are breaking down. Waters are polluted, soils depleted, forests stripped bare.

At the root of this unraveling is a way of seeing: the belief that humans are separate from nature, and that the rest of life exists as raw material for human desire.

Indigenous worldviews offer another path. They remind us that the world is alive, that every being has agency, and that thriving requires reciprocity. This mindset is not just for Indigenous communities; it is a lesson for all of us. If we do not re-learn how to see the world as alive, we risk killing the very systems that sustain us.

Toward a Different Future

Imagine what might change if we shifted our grammar. Instead of asking, “What is this land worth?” we might ask, “How is this land living?” Instead of calculating “how many board feet of timber” stand in a forest, we might ask, “How is the forest foresting? Who is sheltered, fed, and healed here?”

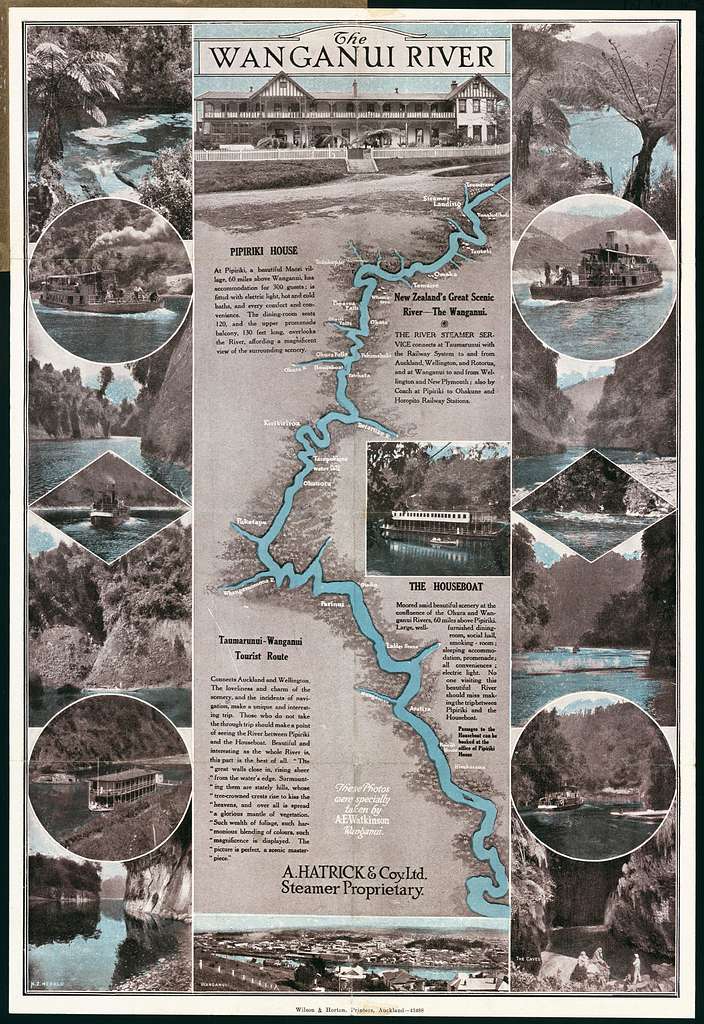

This small shift in language could ripple outward into ethics, economics, and politics. Laws might protect rivers as legal persons, as has already happened in New Zealand with the Whanganui River. Conservation might move beyond “resource management” into kinship care. Agriculture might stop treating soil as “dirt” and begin honoring it as a living community.

Indigenous teachings remind us that our well-being is tied to the well-being of all beings. To thrive as humans, we must ensure that the forests, waters, animals, and soils are thriving too. In this way, Indigenous worldviews are not only about cultural survival – they are about planetary survival.

The Gift of Another Way

What does it mean to live as if the world is alive?

It means walking more gently.

It means taking less, and giving more.

It means treating other beings not as “its” but as relatives.

It means remembering that our lives are bound up in theirs.

In English, we say “to be alive.” In Potawatomi, the whole world is alive-ing. When we speak this way, even imperfectly, even in English – we begin to reawaken a deeper truth: that humans are nature, and nature is us.

The Indigenous gift is not simply a reminder of what was lost. It is a guide to what could still be regained – a world where reciprocity replaces extraction, where relationships replace ownership, where the Earth is not an object but a beloved community of peoples.